We all know that snoring is complicated, as evidenced by the difficulty most people have in solving it. The complexity and mystery originate from the impression that snoring is the noise from a restricted airway’s interference with breathing airflow. But where is the restriction located and how can it be alleviated so that a patient will stop snoring?

To best evaluate dental patients who present with complaints of snoring, it’s important for clinicians to understand the complexities of breathing during sleep.

The Big Mysteries of Snoring

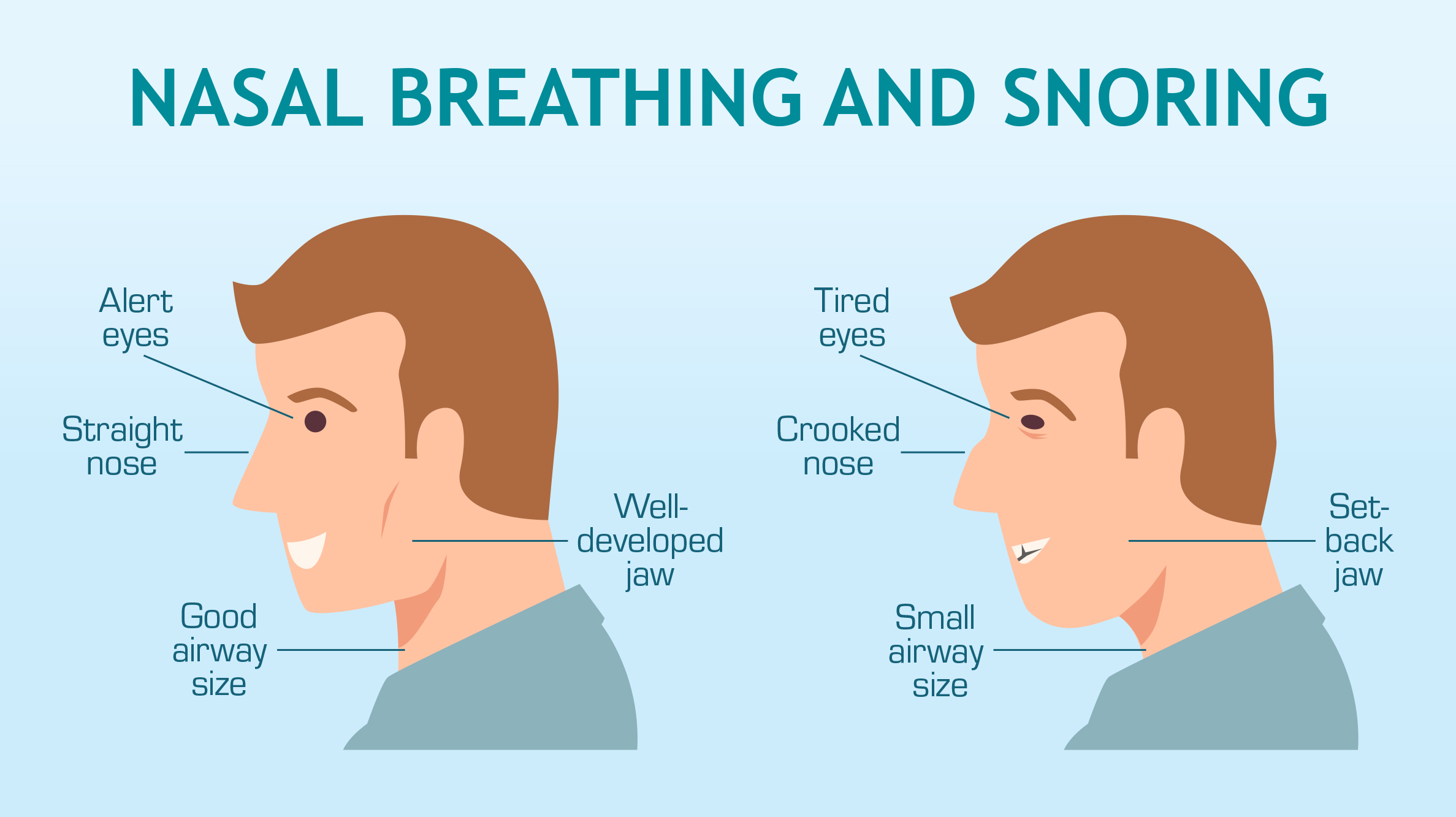

Mystery No. 1: Snoring noise is usually produced by breathing through the oral airway. Consequently, the first big mystery is the mistaken belief that the mouth is the cause of snoring. Counterintuitively, the actual cause is nasal airway obstruction, which triggers oral breathing and, consequently, snoring’s noise.

During sleep, the brain is wired to respond to very slight reductions in inspiratory nasal flow. A minuscule drop in inspiratory nasal airflow pressure alerts the brain to convert to oral breathing to compensate for diminished airflow and oxygen intake. Once oral breathing commences, the mouth drops open and the tongue drops back into the airway. Because the mouth is not designed for breathing, the mucosal layer of the oral airway dries out. As airflow passes through the dry orifice, it causes friction on the surfaces of the dry and slack tongue and throat. This leads to vibration, movement and the sounds of restricted breathing. (Think of a wind instrument and its vibrating reed leading to sound.)

So, if a primary cause of snoring is nasal obstruction that forces a switch from nasal to oral breathing, then opening the nasal airway, and restoring nasal patency to maximize nasal breathing, is the critical initial action in solving a patient’s snoring. To stop snoring, successful nasal breathing is an important — and often overlooked — key.

Easy, non-prescription options in the restoration of nasal airway patency are the soft medical-grade nasal stents, Max-Air® Nose Cones® and Sinus Cones®. According to research published in the journal CHEST, nasal obstruction from any cause predisposes a person to sleep-disordered breathing. Anyone who has been told that they snore when they have a head cold or nasal allergies is quite familiar with this scenario.

Mystery No. 2: There is the mistaken belief that all snorers are the same. They are not — and with a few simple health history questions and chairside evaluations, snorers can be segmented into a few simple groups to assist in identifying simpler versus more difficult cases.

Consider that nasal and oral airway obstruction can be due to the following:

- Structural anomalies of the airway (related to genetics, development or trauma)

- Age-related changes to the airway (reduction of muscle tone and epidermis resiliency, weight loss or weight gain)

- A combination of both of the above (structural and age-related changes)

By looking a little closer at the anatomy of the nasal and oral airway, it is possible to demystify the causes, and as a result devise a better solution.

How to Stop Snoring: Where to Start?

To provide an anti-snoring solution for your patients, begin by asking them this one simple question: “How long have you been snoring?” The response — segmented into groups below — will help you determine the ideal treatment.

- Group A: Patients who have been snoring since they were children or young adults without trauma (e.g., broken nose from a fall or sports) may be classified as more complex developmental structural snorers.

- Group B: Patients who have been snoring since they were children or young adults with trauma may be classified as simple structural snorers.

- Group C: Patients who have started snoring more recently, as grown or older adults, may be classified as age-related snorers.

- Group D: Patients who have snored since they were children, but have now progressed to constant and loud snoring may be classified as having a combination of complex developmental structural concerns with compounding age-related factors.

Discussion

The more complex patient case will be the developmental anomaly structural snorer: Group A.

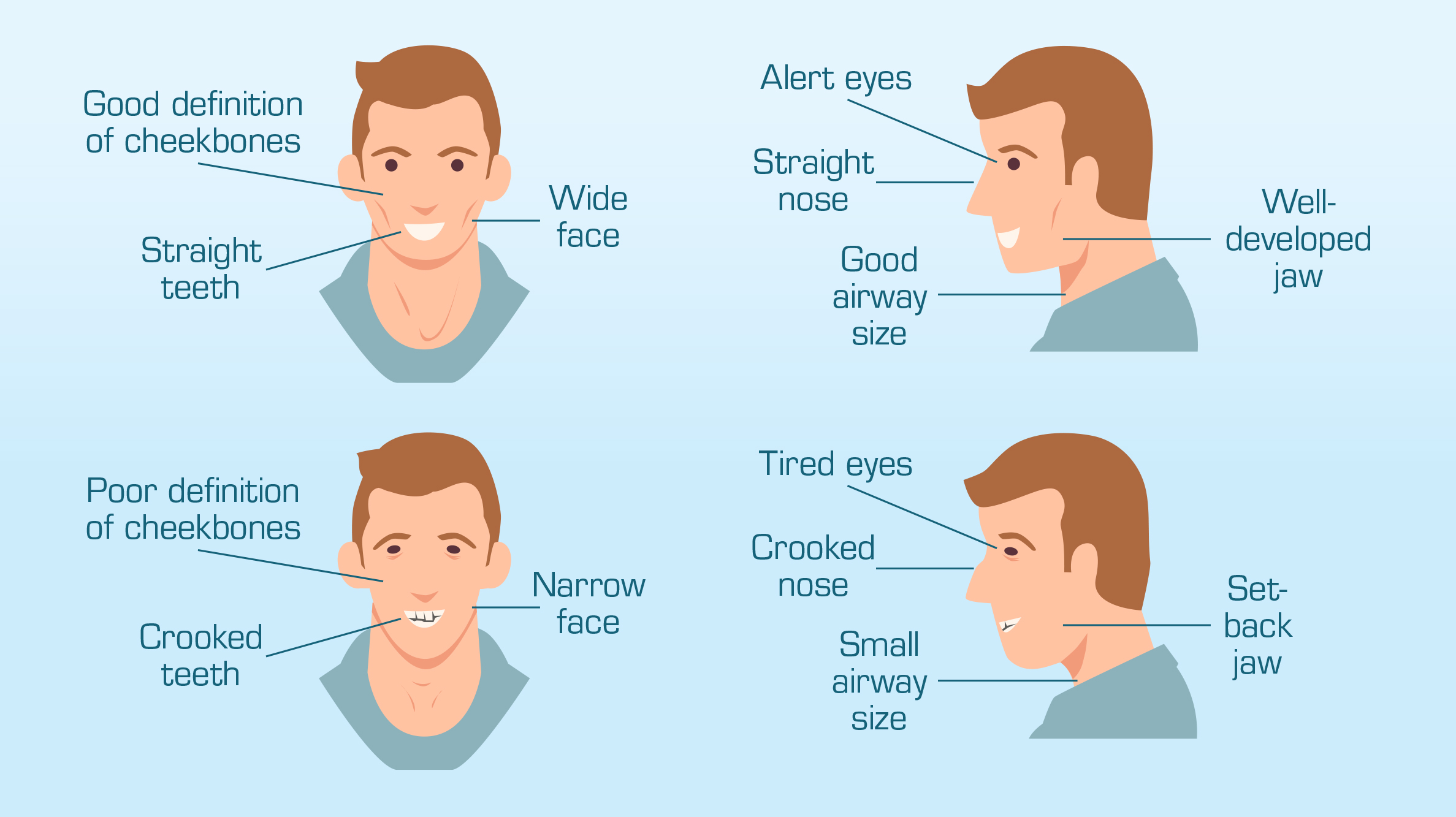

This patient presents with nasal airway obstruction in the form of a more severe deviated nasal septum, sometimes a genetically inadequate nose for their body size, crooked teeth, missing teeth, a high narrow palate, or an underdeveloped facial structure. Occasionally, this patient may have had four-bicuspid extraction (due to teeth crowding from oral breathing) and an orthodontically retracted and narrowed palate (i.e., small horseshoe-shaped dentition).

Since the nasal airway was restricted because of the septal deviation, the oral airway didn’t develop correctly as the patient grew. As an adult, this patient’s oral airway and soft palate are typically too small for their tongue, which then occludes the airway. This patient may also be retrognathic (the mandible is set back further than the maxilla) to a greater or lesser extent, which further compromises the airway. This patient’s airway restriction and snoring is due to multiple layers of airway compromise and is going to be a more complicated case.

This patient may require treatment with an oral sleep appliance and nasal device.

The simpler patient case will be the age-related snorer: Group C.

This patient presents with nasal airway obstruction in the form of nasal sidewall collapse (sometimes only visible upon inspiration) and a mild septal deviation; reduced skin elasticity around the nose, mouth and throat; and potentially excess weight in the face and around the neck. The sidewall collapse of the nose during sleep, coupled with laxity of facial structures — potentially heavier with excess weight — closes off the nasal airway and crowds the oral airway space. Oral breathing is triggered and, consequently, snoring occurs.

Nasal collapse can be easily identified by 1) asking the patient to inhale deeply and quickly through the nose (mouth closed) and 2) watching the sidewalls of the nose collapse inward. Even a small amount of nasal sidewall collapse can be problematic during sleep, as the small muscles of the face and nose relax and make nasal collapse more pronounced. By using the Max-Air Nose Cones to address the nasal obstruction, and an oral appliance to relieve oropharynx airway crowding from excess weight and skin laxity, treating the age-related snorer is usually simple and straightforward.

The slightly more involved patient case is the trauma-related, simple structural anomaly snorer: Group B.

This patient presents with a history of mild or infrequent snoring and a memorable trauma to the nose or face. Sometimes this patient isn’t bothered by snoring, but feels that breathing is impaired, especially during sleep or sports. Depending on the location of the trauma (e.g., a broken or damaged nose, or dislodged tooth or teeth), signs of developmental anomalies may be visible. A slight deviated septum, mild bite changes, and misaligned centerlines are a few common occurrences, especially if they are milder in form.

Solving this patient’s airway issue can often be achieved by using a Max-Air nasal dilator (to relieve nasal obstruction) or an oral appliance (to correct oropharynx patency issues).

The most involved and complicated patient case is the complex structural anomaly coupled with age-related factors: Group D.

This patient presents with a history of habitual snoring, which has increased in frequency and volume. Although the patient may not suffer with apnea (a complete cessation in breathing), the patient may be disturbed by snoring and struggling with unrestorative sleep.

This patient is the most difficult to treat because of the impairment of so many confounding factors. Treatment plans are best devised with a team of experts because surgical or device intervention may need to be staged. Treatment may include nasal surgery, palatal expansion, nasal device or oral appliance intervention, positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy, or nerve stimulation therapy.

Conclusion

This article attempts to briefly identify broad categories of airway-compromised patients to provide starting points to assist in evaluation of your patients — to help them stop snoring. There are many exceptions, special cases, outliers, and other considerations that come into play with airway issues. When in doubt, refer out or contact your dental laboratory with questions.

To learn more about oral appliance therapy, and to explore the New West family of sleep appliances, click here.